The wheel and tyre Bible - everything you need to know about tyre markings, wheels, tyres (tires), rim sizes, tread depth and wear, aquaplaning, wheel balancing, aftermarket wheels, alloy wheels, TPMS tire pressure monitoring systems and much more.

Win free stuffWhat's New?e-Book / Images

Win free stuffWhat's New?e-Book / Images![[All you need to know about car tyres (Tires) and Wheels.]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/thewheelandtyrebible.gif)

| I am in no way affiliated with any branch of the motor industry. I am just a pro-car, pro-motorbike petrolhead who is into basic maintenance. This information is the result of information-gathering, research and hands-on experience. By reading these pages, you agree to indemnify, defend and hold harmless Christopher J Longhurst, any sponsors and/or site providers against any and all claims, damages, costs or other expenses that arise directly or indirectly from you fiddling with your car or motorbike as a result of what you read here. In short: the advice here is worth as much as you are paying for it. |

Translated versions of this site:  Русский (Russian)

Русский (Russian)

Page 1 ------ Page 2

Moving on - Wheel measurements.

Okay. If you want to change the wheels on your car, you need to take some things into consideration.

- Number of bolts or studs

It goes without saying that you can't fit a 4-bolt wheel onto a 5-bolt wheel hub. Sounds obvious, but people have been known to fork out for an expensive set of alloy wheels only to find they've got the wrong number of mounting holes. - Pitch Circle Diameter

Right. So you know how many holes there are. Now you need to know the PCD, or Pitch Circle Diameter. This is the diameter of the invisible circle formed by scribing a circle that passes through the centre point of each mounting hole. If you've got the right number of holes, but they're the wrong spacing, again the wheel just won't fit. - PCD notation

Stud patterns and PCD values are typically listed in this notation : 5x114.42. This means a 5-bolt pattern on an imaginary circle of 114.42mm diameter. - Centre spigot size

This is a tricky one. The wheel bolts or studs are there to hold the wheel laterally on to the axle, but they're not really designed to take vertical load - ie. they're not designed to take the weight of the car. That's the job of the centre spigot - the part of the axle that sticks out and pokes through the hole in the middle of the wheel. It's the load-bearing part of the axle and the wheel, as well as being the assembly that centres the wheel on the axle. For the most part, the centre spigot on aftermarket alloy wheels is much larger than that of the car you want to put them on to. When this happens, the best solution is a spigot locating ring (also called a hub-centric ring) which is essentially a steel or hard plastic doughnut designed to fit snugly on to your axle spigot and into the wheel spigot.

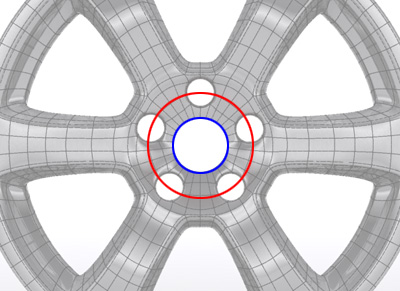

The image below shows the PCD (the red ring and mounting hole centrelines) and the spigot size (the blue ring). The spigot hole on an alloy wheel is normally covered up with a centre cap or cover.

- Inset or outset

This is very important. Ignore this and you can end up with all manner of nasty problems. This is the distance in mm between the centre line of the wheel rim, and the line through the fixing face. You can have inset, outset or neither. This determines how the suspension and self-centring steering behave. The most obvious problem that will occur if you get it wrong is that the steering will either become so heavy that you can't turn the car, or so light that you need to spend all your time keeping the bugger in a straight line. More mundane problems through ignoring this measurement can range from wheels that foul parts of the bodywork or suspension, to high-speed judder in the steering because the suspension setup can't handle that particular type of wheel. This figure will be stamped on the wheel somewhere as an ET figure.

Inset and outset are subsets of offset and the relationship is this : positive offset = inset. Negative offset = outset. Typically you can get away with 5mm-7mm difference from the vehicle manufacturer specification before you'll run into trouble with the wheels fouling the suspension or bodywork. So for example if your stock wheels have an offset of 42mm and you can only find replacements with a 40mm offset, that 2mm difference ought to OK.

| No offset | Inset wheel | Outset wheel |

|---|---|---|

![[none]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/no_offset.gif) |

![[inset]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/inset_wheel.gif) |

![[outset]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/outset_wheel.gif) |

- More inset = closer to the suspension?

It may sound counterintuitive, but when you increase the inset of a wheel, you decrease the clearance between the inner edge of the wheel and the suspension components. In the example below, the red wheel has a larger inset - ie. the distance from the mounting face to the centreline of the wheel is larger than that of the green wheel. The grey blocks indicate a stylised mounting hub, axle and suspension component. You can see that by increasing the inset (positive offset) of the wheel, it pushes the inner edge of the wheel and tyre closer to the suspension. Conversely, decreasing the inset moves the wheel and tyre closer to the outside of the vehicle where it might scrub and rub against the bodywork and wheel arches. It might help to think of this more in terms of overall offset rather than inset and outset. The most positive the offset, the more the wheel is tucked into the car. The more negative the offset, the more the wheel sticks out.

- A real example

![[arealwheel]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/arealwheel.jpg) They say a picture is equivalent to a thousand words, so study this one

carefully. It's one of the alloy wheels off one of my old cars.

Enlarged so you can read it is the wheel information described above.

You'll notice it reads "6J x 14 H2 ET45". The "6J x 14" part of that is

the size of the wheel rim - in this case it has a depth of 6 inches and

a diameter of 14 inches (see the section directly below here on wheel

sizes for a more in-depth explanation). The "J" symbolises the shape of

the tyre bead profile. (see rim contours below)

They say a picture is equivalent to a thousand words, so study this one

carefully. It's one of the alloy wheels off one of my old cars.

Enlarged so you can read it is the wheel information described above.

You'll notice it reads "6J x 14 H2 ET45". The "6J x 14" part of that is

the size of the wheel rim - in this case it has a depth of 6 inches and

a diameter of 14 inches (see the section directly below here on wheel

sizes for a more in-depth explanation). The "J" symbolises the shape of

the tyre bead profile. (see rim contours below)

The "H2" means that this wheel rim is a double hump design (see hump profiles, below). The "ET45" figure below that though symbolises that these wheels have a positive offset of 45mm. In other words, they have an inset of 45mm. In my case, the info is all stamped on the outside face of the wheel which made it nice and easy to photograph and explain for you. On most aftermarket wheels, they don't want to pollute the lines and style of the outside of the wheel with stamped-on information - it's more likely to be found inside the rim, or on one of the inner mounting surfaces.

The wheel offset calculator

This little javascript will help you to understand the different between your old and new wheel and tyre combination in terms of the offset and how it's going to affect the overall lateral position of the wheel and tyre.

Matching your tyres to your wheels.

Okay. This is a biggie so take a break, get a hot cup of Java, relax and then when you think you're ready to handle the complexities of tyre matching, carry on. This diagram should help you to figure out what's going on.

![[xsection]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/xsection.gif)

Wheel sizes

Wheel sizes are expressed as WWWxDDD sizes. For example 7x14. A 7x14 wheel is has a rim width of 7 inches, and a rim diameter of 14 inches. The width is usually below the width of the tyre for a good match. So a 185mm tyre would usually be matched to a wheel which is 6 inches wide. (185mm is more like 7 inches, but that's across the entire tyre width, not the bead area where the tyre fits the rim.)

Rolling Radius

The important thing that you need to keep in consideration is rolling radius. This is so devastatingly important that I'll mention it in bold again:rolling radius!.

This is the distance in mm from the centre of the wheel to the edge of

the tread when it's unladen. If this changes because you've mismatched

your new wheels and tyres, then your speedo will lose accuracy and the

fuel consumption might go up. The latter reason is because the

manufacturer built the engine/gearbox combo for a specific rolling

radius. Mess with this and the whole thing could start to fall down

around you.

It's worth pointing out that the actual radius the

manufacturers use for speedo calculation is the 'dynamic' or the

'laden' radius of the wheel at the recommended inflation pressure and

'normal' loading. Obviously though, this value is entirely dependent on

the unladen rolling radius.

J, JJ, K, JK, B, P and D : Tyre bead profiles / rim contour designations.

![[beadprofile]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/beadprofile.gif) No, my keyboard letters weren't stuck down when I typed this. The

letter that typically sits between the rim width and diameter figures

stamped on the wheel, and indicates the physical shape of the wheel

where the tyre bead meets it. In the cross-section on the left you can

see the area highlighted in red.

No, my keyboard letters weren't stuck down when I typed this. The

letter that typically sits between the rim width and diameter figures

stamped on the wheel, and indicates the physical shape of the wheel

where the tyre bead meets it. In the cross-section on the left you can

see the area highlighted in red.

Like so many topics, the answer as to which letter represents which

profile is a long and complicated one. Common wisdom has it that the

letter represents the shape. ie. "J" means the bead profile is the

shape of the letter "J". Not so, although "J" is the most common

profile identifier. 4x4 vehicles often have "JJ" wheels. Jaguar

vehicles (especially older ones) have "K" profile wheels. Some of the

very old VW Beetles had "P" and "B" profile wheels.

Anyway the reason it is an "awkward topic to find definitive data on"

is very apparent if you've ever looked at Standards Manual of the

European Tyre and Rim Technical Organisation. It is extremely

hard to follow! There are pages and pages (64 in total) on wheel

contours and bead profiles alone, including dimensions for every type

of wheel you can think of (and many you can't) with at least a dozen

tabled dimensions for each. Casually looking through the manual is

enough to send you to sleep. Looking at it with some concentration is

enough to make your brain run out of your ears. To try to boil it all

down for you, it seems that they divide up the rim into different

sections and have various codes to describe the geometry of each area.

For example, the "J" code makes up the "Rim Contour" and specifies rim

contour dimensions in a single category of rims called "Code 10 to 26

on 5deg. Drop-Centre Rims". To give you some idea of just how complex /

anal this process is, I've recreated one such diagram with Photoshop

below to try to put you off the scent.

From the tables present in this manual, the difference in dimensions

between "J" and "B" rims is mainly due to the shape of the rim flange.

This is the part in the above diagram defined by the R radius and B and

Pmin parameters. Hence my somewhat simpler description : tyre bead profiles.

Note

that in my example, the difference between "J" and "B" rims is small

but not negligible. This area of rim-to-tyre interface is very

critical. Very small changes in a tyre's bead profile make large

differences in mounting pressures and rim slip.

"A" and "D" contour

designations come under the category of "Cycles, Motorcycles, and

Scooters" but also show up in the "Industrial Vehicles and Lift Trucks"

category. Naturally, the contours have completely different geometry

for the same designation in two different categories.

The "S", "T", "V" and "W" contour designation codes fall into the

"Commercial Vehicles, Flat Base Rims" category. The "E", "F", "G" and

"H" codes fall into the "Commercial Vehicles, Semi-Drop Centre Rims"

category. Are you beginning to see just how complex this all is?

I think the best thing for you, dear reader, is a general rule-of-thumb, and it is this : if your wheels are stamped 5J15 and you buy 5K15 tyres, rest assured they absolutely won't fit.

H, H2, FH, CH, EH and EH2 : Hump profiles.

More alphabet soup. So you might have just about understood the bit about bead profiles, but there's another design feature of wheel rims. The 'hump' is actually a bump put on the bead seat (for the bead) to prevent the tyre from sliding off the rim while the vehicle is moving. As with rim contours, there are several different designations of hump design and configuration, depending on the number and shape of the humps. For the inquisitive reader, here's a table of the hump designations, and a diagram similar to the one above which displays in nauseating detail just what a hump really is. The eagle-eyed amongst you (or those paying attention) will notice that this diagram is an enlarged view of the area around Pmin in the other ETRTO diagram above, because that's typically where the hump is.

| Designation | Bead Seat Contour | Marking | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outside | Inside | ||

| Hump | Hump | Normal | H |

| Double Hump | Hump | Hump | H2 |

| Flat Hump | Flat Hump | Normal | FH |

| Double Flat Hump | Flat Hump | Flat Hump | FH2 |

| Combination Hump | Flat Hump | Hump | CH |

| Extended Hump | Extended Hump | Extended Hump | EH2 |

| Extended Hump 2+ | Extended Hump 2+ | Extended Hump 2+ | EH2 + |

If you're obsessive-compulsive and absolutely must know everything there is to know about bead profiles, humps and rim flanges, you can check out the ETRTO (European Tyre and Rim Technical Organisation website from where you can purchase their manuals and documents. Go nuts. Meanwhile, the rest of us will move on to the next topic.

Why would I want to change to alloy wheels and new tyres anyway?

A good question. Styling and performance are the only two reasons. Most cars come with horrible narrow little tyres and 13 inch rims. More recently the manufacturers have come to their senses and started putting decent combinations on factory cars so that's not so much of a problem any more. The first reason is performance. Speed in corners more specifically. If you have larger rims, you get smaller sidewalls on the tyres. And if you have smaller sidewalls, the tyre deforms less under the immense sideways forces involved in cornering.

So how does it all figure out?

Point to note: 1 inch = 25.4mm. You need to know that because tyre/wheel manufacturers insist on mixing mm and inches in their ratings.

Also note that a certain amount of artistic licence is required when

calculating these values. The tyre's rolling radius will change the

instant you put load on it, and calculating values to fractions of a

millimetre just isn't worth it - tyre tread wear will more than see off

that sort of accuracy.

Lets take an average example: a car with factory fitted 6x14 wheels and 185/65 R14's on them.

- Radius of wheel = 7 inches (half the diameter) = 177.8mm

- Section height = 65% of 185mm = 120.25mm

- So the rolling radius for this car to maintain is 177.8+120.25=298.05mm

With me so far? Good. Now lets assume I want 15 inch rims which are slightly wider to give me that nice fat look. I'm after a set of 7x15's

First we need to determine the ideal width of tyre for my new wider

wheels. 7 inches = 177.8mm. The closest standard tyre width to that is

actually 205mm so that's what we'll use. (remember the tyre width is

larger than the width of the bead fitting.)

- Radius of wheel = 7.5 inches (half of 15) = 190.5mm

- We know that the overall rolling radius must be as close to 298.05mm as possible

- So the section height must be 298.05mm-190.5mm = 107.55mm

- Figure out what percentage of 205mm is 107.55mm. In this case it's 52.5%

- So combine the figures - the new tyre must be 205/50 R15

- ....giving a new rolling radius of 293mm - more than close enough.

A tyre size calculator.

Well if all that maths seems a little beyond you, and judging by the volume of e-mails I get on this subject, it might well be, I've made a little Javascript application below to help you out. Select the tyre size you currently have, and then the size you're interested in. Calculate each tyre size and then click on the click to calculate the difference button. It will show you all the rolling radii, circumferences, percentage differences and even speedometer error. Enjoy.

A Speedometer error means an odometer error too.

It stands to reason that if you change the rolling radius of your wheels and tyres, and the speedometer no longer reads correctly, that your odometer will also gradually become inaccurate. Assume for example that you bought a car brand new and changed the wheels and tyres on day one from 195.65R14 to 205/50R15 - not an uncommon change. By the calculator above, that makes your speedometer over read by 1.7%. Consequently, the registered odometer reading will also be out by the same value. So for example, when you get to 10,000km of driving (in the real world), your odometer will actually read 10,170km. OK so that's not a huge difference but it is one of the reasons why most car dealers have a disclaimer on their secondhand vehicles telling you that they won't guarantee the displayed mileage. ("Clocking" the odometer is the other reason). Odometer errors due to mis-matched tyres and wheels will happen on regular odometers as well as the newer digital ones.

A quick word about motorcycle speedometers.

Veering off-topic for a moment, it's worth pointing out that without exception, all motorbike speedometers are designed to inflate the ego of the rider by at least 5%. In some cases, they are are much as 10% optimistic. ie. the speedometer on a motorbike will always over-read. 100mph? Not likely - you're actually doing closer to 90mph.

Aspect Ratio and Rim / Pan Width.

Aspect ratio is, as you know if you read the bit above, the ratio of

the tyre's section height to its section width. The aspect ratio is

sometimes referred to as the tyre 'series'. So a 50-series tyre means

one with an aspect ratio of 50%. The maths is pretty simple and the

resulting figure is stamped on all tyres as part of the sizing

information:

Aspect ratio is, as you know if you read the bit above, the ratio of

the tyre's section height to its section width. The aspect ratio is

sometimes referred to as the tyre 'series'. So a 50-series tyre means

one with an aspect ratio of 50%. The maths is pretty simple and the

resulting figure is stamped on all tyres as part of the sizing

information:

| Aspect ratio = | Section height |

| Section width |

The actual dimensions of a tyre depend on the rim on which it is

mounted. The biggest variable is the tyre's section width; a change of

about 0.2" for every 0.5" change in rim width.

The ratio between the section width and the rim width is pretty

important. If the rim width is too narrow, you pinch the tyre in and

cause it to balloon more in cross-section. If the rim width is too

wide, you run the risk of the tyre ripping away at high speed.

For 50-series tyres and above, the rim width is 70% of the tyre's section width, rounded off to the nearest 0.5.

For example, a 255/50R16 tyre, has a design section width of 10.04"

(255mm = 10.04 inches). 70% of 10.04" is 7.028", which rounded to the

nearest half inch, is 7". Ideally then, a 255/50R16 tyres should be

mounted on a 7x16 rim.

For 45-series tyres and below, the rim width is 85% of the tyre's section width, rounded off to the nearest 0.5.

For example, a 255/45R17 tyre, still has a design section width of

10.04" (255mm = 10.04 inches). But 85% of 10.04" is 8.534", which

rounded to the nearest half inch, is 8.5". Ideally then, a 255/45R17

tyre should be mounted on an 8½x17 rim.

Sources: ETRTO Design manual. Yokohama Tyres

An ideal rim-width calculator

Blimey I'm good to you. Can't figure that maths out either? Click away my friend and Chris's Rimwidthulatortm will tell you what you need to know. Obvious disclaimer : the results should be verified with the tyre dealership/manufacturer.

Too wide or too narrow - does it make a difference?

Given all the information above, you ought to know one last thing.

A rim that is too narrow in relation to the tyre width will allow the

tyre to distort excessively sideways under fast cornering. On the other

hand, unduly wide rims on an ordinary car tend to give rather a harsh

ride because the sidewalls have not got enough curvature to make them

flex over bumps and potholes. That's why there is a range of rim sizes

for each tyre size in my Rimwidthulator above. Put a 185/65R14 tyre on

a rim narrower than 5inches or wider than 6.5inches and suffer the

consequences.

The Plus One concept

The plus one concept describes the proper sizing up of a wheel and tyre combo without all that spiel I've gone through above. Basically, each time you add 1 inch to the wheel diameter, add 20mm to the tyre width and subtract 10% from the aspect ratio. This compensates nicely for the increases in rim width that generally accompany increases in diameter too. By using a larger diameter wheel with a lower profile tyre it's possible to properly maintain the overall rolling radius, keeping odometer and speedometer changes negligible. By using a tyre with a shorter sidewall, you gain quickness in steering response and better lateral stability. The visual appeal is obvious, most wheels look better than the sidewall of the tyre, so the more wheel and less sidewall there is, the better it looks.

![[plusone]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/plusone.gif)

Tyre size table up to 17" wheels

Here, for those of you who can't or won't calculate your tyre size, is a table of equivalent tyres. These all give rolling radii within a few mm of each other and would mostly be acceptable, depending on the wheel rim size you're after.

| 80 SERIES | 75 SERIES | 70 SERIES | 65 SERIES | 60 SERIES | 55 SERIES | 50 SERIES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135/80 R 13 | - | 145/70 R 13 | - | 175/60 R 13 | - | - |

| - | - | 155/70 R 13 | 165/65 R 13 | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 175/65 R 13 | - | - | - |

| 145/80 R 13 | - | 155/70 R 13 | 175/65 R 13 | 185/60 R 13 | 185/55 R 14 | - |

| - | - | 165/70 R 13 | 165/65 R 14 | 175/60 R 14 | - | - |

| - | - | 175/70 R 13 | - | - | - | - |

| 155/80 R 13 | 165/75 R 13 | 175/70 R 13 | 165/65 R 14 | 175/60 R 14 | 195/55 R 14 | 195/50 R 15 |

| - | - | 185/70 R 13 | 175/65 R 14 | 185/60 R 14 | 185/55 R 15 | - |

| - | - | 165/70 R 14 | - | 195/60 R 14 | - | - |

| 165/80 R 13 | - | 185/70 R 13 | 175/65 R 14 | 195/60 R 14 | 205/55 R 14 | 205/50 R 15 |

| - | - | 165/70 R 13 | 185/65 R 14 | 205/60 R 14 | 185/55 R 15 | 195/50 R 16 |

| - | - | 175/70 R14 | - | - | 195/55 R 15 | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 205/55 R15 | - |

| 175/80 R 13 | 175/75 R 14 | 175/70 R 14 | 185/65 R 14 | 205/60 R 14 | 195/55 R 15 | 215/50 R 16 |

| - | - | 185/70 R 14 | 195/65 R 14 | 215/60 R 14 | 205/55 R 15 | 195/50 R 16 |

| - | - | - | 185/65 R 15 | 195/60 R 15 | - | 205/50 R 16 |

| 185/80 R 13 | 185/75 R 14 | 185/70 R 14 | 195/65 R 14 | 215/60 R 14 | 205/55 R 16 | 205/50 R 16 |

| - | - | 195/70 R 14 | 185/65 R 15 | 225/60 R 14 | - | 225/50 R 16 |

| - | - | - | 195/65 R 15 | 195/60 R 15 | - | 205/50 R 17 |

| - | - | - | - | 205/60 R 15 | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | 215/60 R 15 | - | - |

So that's it then?

Yes - that's it. A little time with a calculator, a pen and some paper will enable to you confidently stride into your local tyre/wheel supplier and state exactly what you want.

A Case study to help you out

Lead by example - that's a good motto. My Case Study will walk you through the entire process of selecting a new set of wheels and tyres so you can get an idea of what is involved.

Oversizing tyres

If you want the fat look but don't want to go bonkers with new wheels, you can oversize the tyres on the rims usually by about 20mm (to be safe). So if your standard tyres are 185/60 R14s, you can oversize them to about 205mm. But make sure you recalculate the percentage value to keep the sidewall height the same.

Fitment guides

Rochford Tyres

has an excellent fitment guide page where they list a ton of

combinations and permutations of wheels and tyres for all the popular

makes and models. The guide is designed to give you an idea of wheel

and tyre sizes that will keep you close to spec for rolling radius. Use

the 'Alloy Wheel Search' box at the top-left of their site. As an added

bonus, if you decide to buy anything from them, use the

Rochford Tyres

has an excellent fitment guide page where they list a ton of

combinations and permutations of wheels and tyres for all the popular

makes and models. The guide is designed to give you an idea of wheel

and tyre sizes that will keep you close to spec for rolling radius. Use

the 'Alloy Wheel Search' box at the top-left of their site. As an added

bonus, if you decide to buy anything from them, use the  at the checkout to get 5% off! Sweet!

at the checkout to get 5% off! Sweet!

And finally, you might like to check out this little program written by Brian Cassidy,which helps with tyre size calculation.

| Like the site? Help Chris buy a bike. The page you're reading is free, but if you like what you see and feel you've learned something, throw me a $5 bone as a token of your appreciation. Help me buy the object of my desire. |

Fat or thin? The question of contact patches and grip.

If there's one question guaranteed to promote argument and counter argument, it's this : do wide tyres give me better grip?

Fat tyres look good. In fact they look stonkingly good. In the dry they

are mercilessly full of grip. In the wet, you might want to make sure

your insurance is paid up, especially if you're in a rear-wheel-drive

car. Contrary to what you might think (and to what I used to think),

bigger contact patch does not necessarily mean increased grip. Better yet, fatter tyres do not mean bigger contact patch. Confused? Check it out:

Pressure=weight/area.

That's about as simple a physics equation as you can get. For the

general case of most car tyres travelling on a road, it works pretty

well. Let me explain. Let's say you've got some regular tyres, as

supplied with your car. They're inflated to 30psi and your car weighs

1500Kg. Roughly speaking, each tyre is taking about a quarter of your

car's weight - in this case 375Kg. In metric, 30psi is about 2.11Kg/cm².

By that formula, the area of your contact patch is going to be roughly 375 / 2.11 = 177.7cm² (weight divided by pressure)

Let's say your standard tyres are 185/65R14 - a good middle-ground,

factory-fit tyre. That means the tread width is 18.5cm side to side. So

your contact patch with all these variables is going to be about

177.7cm² / 18.5, which is 9.8cm. Your contact patch is a rectangle

18.5cm across the width of the tyre by 9.8cm front-to-back where it

sits 'flat' on the road.

Still with me? Great. You've taken your car to the tyre dealer and with

the help of my tyre calculator, figured out that you can get some

swanky 225/50R15 tyres. You polish up the 15inch rims, get the tyres

fitted and drive off. Let's look at the equation again. The weight of

your car bearing down on the wheels hasn't changed. The PSI in the

tyres is going to be about the same. If those two variables haven't

changed, then your contact patch is still going to be the same :

177.7cm²

However

you now have wider tyres - the tread width is now 22.5cm instead of

18.5cm. The same contact patch but with wider tyres means a narrower

contact area front-to-back. In this example, it becomes 177.7cm² /

22.5, which is 7.8cm.

|

| Imagine driving on to a glass road and looking up underneath your tyres. This is the example contact patch (in red) for the situation I explained above. The narrower tyre has a longer, thinner contact patch. The fatter tyre has a shorter, wider contact patch, but the area is the same on both. |

And there is your 'eureka' moment. Overall, the area of your contact patch has remained more or less the same. But by putting wider tyres on, the shape of the contact patch has changed. Actually, the contact patch is really a squashed oval rather than a rectangle, but for the sake of simplicity on this site, I've illustrated it as a rectangle - it makes the concept a little easier to understand. So has the penny dropped? I'll assume it has. So now you understand that it makes no difference to the contact patch, this leads us on nicely to the sticky topic of grip.

The area of the contact patch does not affect the actual grip of the tyre. The things that do

affect grip are the coefficient of friction of the rubber compound and

the load on the tyre. As far as friction is concerned, the formula is

relatively simple - F=uN, where F is the frictional force, N is the

Normal force for the surfaces being pressed together and u is the

coefficient of friction. In the case of a tyre, the Normal force

basically stays the same - mass of the car multiplied by gravity. The

coefficient of friction also remains unchanged because it's dependent

on the two surfaces - in this case the road and the tyre's rubber.

The coefficient of friction is in part determined by the rubber

compound's ability to 'key' with the road surface at a microscopic

level.

This explains why you can slide in a corner if you change road surface - for example going from a rough road to a smooth road, or a road surface covered in rain and diesel (a motorcyclist's pet peeve). The slide happens because the coefficient of friction has changed.

So do wider tyres give better grip?

If the contact patch remains the same size and the coefficient of friction and frictional force remain the same, then surely there is no difference in performance between narrow and wide tyres? Well there is but it has a lot to do with heat transfer. With a narrow tyre, the contact patch takes up more of the circumference of the tyre so for any given rotation, the sidewall has to compress more to get the contact patch on to the road. Deforming the tyre creates heat. With a longer contact patch and more sidewall deformation, the tyre spends proportionately less time cooling off than a wider tyre which has a shorter contact patch and less sidewall deformation. Why does this matter? Well because the narrower tyre has less capacity for cooling off, it needs to be made of a harder rubber compound in order to better resist heating in the first place. The harder compound has less mechanical keying and a lower coefficient of friction. The wider tyres are typically made of softer compounds with greater mechanical keying and a higher coefficient of friction. And voila - wider tyres = better grip. But not for the reasons we all thought.

What about lateral force in cornering?

In terms of the lateral force applied to a tyre during cornering, you eventually come to a point where slip angle becomes important. The plot below shows an example of normalised lateral force (in Kg) versus slip angle (in degrees). Slip angle is best described as the difference between the angle of the tyres that you've set by steering, and the direction in which the tyres actually want to travel. As you corner the lateral force increases on your tyres, and at some point, the lateral force is going to overcome the mechanical grip of the tyres and that point is defined by the peak slip angle, as shown in the graph. ie. there comes a point at which no matter how much vertical load is applied to the tyre (from the vehicle weight), it's going to be overcome by the lateral force and 'break away' and slip. So why do wider tyres perform better when cornering? Well apart from the softer rubber compound giving better mechanical keying and a higher coefficient of friction, they have lower profile sidewalls. This makes them more resistant to deforming under lateral load, resulting in a more predictable and stable contact patch. In other words, you can get to a higher lateral load before reaching the peak slip angle.

In reality, trying to figure this out using static examples and reading some internet hack's website is all but impossible because what's really important here is dynamic setup. In reality the contact patch is effectively spinning around your tyre at some horrendous speed. When you brake or corner, load-transfer happens and all the tyres start to behave differently to each other. This is why weight transfer makes such a difference the handling dynamics of the car. Braking for instance; weight moves forward, so load on the front tyres increases. The reverse happens to the rear at the same time, creating a car which can oversteer at the drop of a hat. The Mercedes A-class had this problem when it came out. The load-transfer was all wrong, and a rapid left-right-left on the steering wheel would upset the load so much that the vehicle lost grip in the rear, went sideways, re-acquired grip and rolled over. (That's since been changed.) The Audi TT had a problem too because the load on it's rear wheels wasn't enough to prevent oversteer which is why all the new models have that daft little spoiler on the back.

If your brain isn't running out of your ears already, then here's a link to where you can find many raging debates that go on in the Subaru forums about this very subject. If you decide to read this, you should bear in mind that Simon de Banke, webmaster of ScoobyNet, is a highly respected expert in vehicle dynamics and handling, and is also an extremely talented rally driver. It's also worth noting that he holds the World Record for driving sideways...........

If you decide to fatten up the tyres on your car, another consideration should be clearance with bits of your car. There's no point in getting super-fat tyres if they're going to rub against the inside of your wheel arches. Also, on cars with McPherson strut front suspension, there's a very real possibility that the tyre will foul the steering linkage on the suspension. Check it first!

Holy crap that's complicated. Isn't there a shorter answer?

Yes.

Choose

the dimensions of your tyre according to the 'comfort/cornering speed'

ratio that suits you. Lower profile/series = more precise cornering.

Higher profile/series = more comfort. To increase the contact patch,

lower the tyre pressure a little.

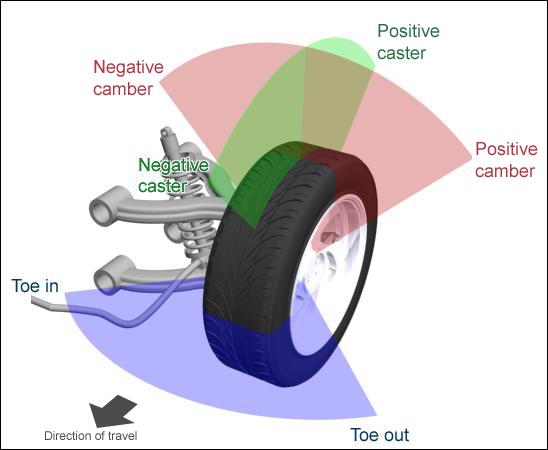

Caster, camber, alignment and other voodoo.

Alignment

This is the general term used to gloss over the next three points:

Caster

This is the forward (negative) or backwards (positive) tilt of the spindle steering axis. It is what causes your steering to 'self-centre'. Correct caster is almost always positive. Look at a bicycle - the front forks have a quite obvious rearward tilt to the handlebars, and so are giving positive caster. The whole point of it is to give the car (or bike) a noticeable centre point of the steering - a point where it's obvious the car will be going in straight line.

Camber

Camber is the tilt of

the top of a wheel inwards or outwards (negative or positive). Proper

camber (along with toe and caster) make sure that the tyre tread

surface is as flat as possible on the road surface. If your camber is

out, you'll get tyre wear. Too much negative camber (wheels tilt

inwards) causes tread and tyre wear on the inside edge of the tyre.

Consequently, too much positive camber causes wear on the outside edge.

Negative camber is what counteracts the tendency of the inside wheel during a turn

to lean out from the centre of the vehicle. 0 or Negative camber is almost always desired.

Positive camber would create handling problems.

The technical reason for this is because when the tyres on the inside

of the turn have negative camber, they will tend to go toward 0 camber,

using the contact patch more efficiently during the turn. If the tyres

had positive camber, during a turn, the inside wheels would tend to

even more positive camber, compromising the efficiency of the contact

patch because the tyre would effectively only be riding on its outer

edge.

Toe in & out

'Toe' is the

term given to the left-right alignment of the front wheels relative to

each other. Toe-in is where the front edge of the wheels are closer

together than the rear, and toe-out is the opposite. Toe-in counteracts

the tendency for the wheels to toe-out under power, like hard

acceleration or at motorway speeds (where toe-in disappears). Toe-out

counteracts the tendency for the front wheels to toe-in when turning at

motorway speeds. It's all a bit bizarre and contradictory, but it does

make a difference. A typical symptom of too much toe-in will be

excessive wear and feathering on the outer edges of the tyre tread

section. Similarly, too much toe-out will cause the same feathering

wear patterns on the inner edges of the tread pattern.

A reader of my site emailed me this which is a nice description of toe-in and toe-out.

As

a front-wheel-drive car pulls itself forwards, the wheels will tend to

pivot arount the king-pins, and thus towards the center of the car. To

ensure they end up straight ahead, they should sit with a slight

toe-out when at rest.

A rear-wheel-drive car pushes itself forward,

and the front wheels are rotated by friction... thus they will tend to

want to trail the king-pins, and therefor will want to splay apart. To

ensure that they run parallel when rolling, they should be given some

toe-in when at rest.

The perfect 4WD car will have neutral pressure

on the front wheels, so have neither toe-in or toe-out... however very

few companies make the perfect 4WD, so some will have a small amount to

toe-in/out, depending on the dominant axle.

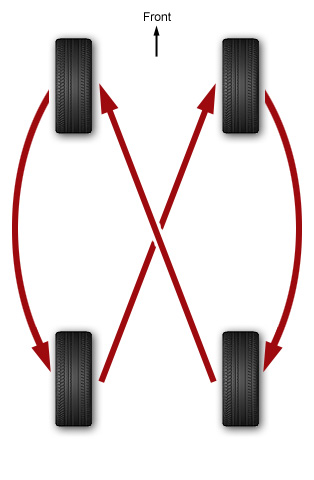

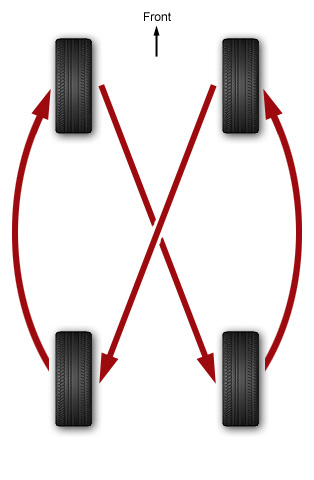

Rotating your tyres.

This is the practice of swapping the front and back tyres to even out

the wear, not the practice of literally spinning your tyres around

(you'd be surprised how often people seem to get confused by this). I

used to believe that this wasn't a good idea. Think about it: the tyres

begin to wear in a pattern, however good or bad, that matches their

position on the car. If you now change them all around, you end up with

tyres worn for the rear being placed on the front and vice versa.

However, having had this done a few times both on front-wheel drive and

all-wheel-drive vehicles during manufacturer services, I' a bit of a

convert. I now reckon it actually is A Good Thing. It results in even overall

tyre wear. By this, I mean wear in the tread depth. This is a valid

point, but if you can't be bothered to buy a new pair of tyres when the

old pair wear too much, then you shouldn't be on the road, let alone

kidding yourself that putting worn front tyres on the back and partly

worn back tyres on the front will cure your problem.

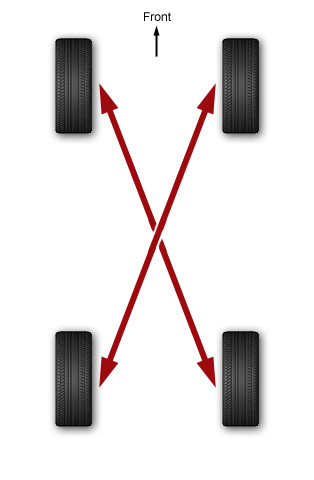

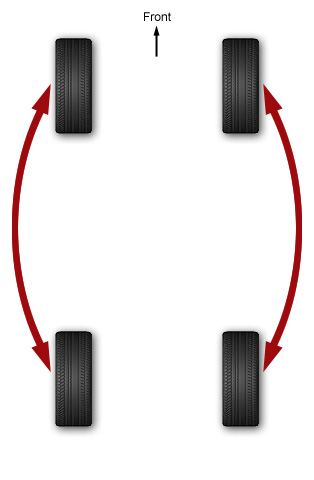

So how should

you rotate your tyres? It depends on whether you have 2-, 4-, front- or

rear-wheel drive, and whether or not you have unidirectional tyres

(meaning, those with tread designed only to spin in one direction).

With unidirectional tyres, you can swap the front and rear per-side,

but not swap them side-to-side. If you do, they'll all end up spinning

the wrong way for the tread. Generally speaking you ought to rotate

your tyres every 5,000 miles (8,000km) or so, even if they're showing

no signs of wear. The following table shows the correct way to rotate

your tyres.

| Front-wheel drive, non-unidirectional tyres | Rear-wheel drive, non unidirectional tyres |

|  |

| 4-wheel drive, non-unidirectional tyres | Any unidirectional tyres |

|  |

Diagnosing problems from tyre wear.

Your tyre wear pattern can tell you a lot about any problems you might be having with the wheel/tyre/suspension geometry setup. The first two signs to look for are over- and under-inflation. These are relatively easy to spot:

![[wear]](tyre_bible_pg2_files/wear_patterns.jpg)

Here's a generic fault-finding table for most types of tyre wear:

| Problem | Cause |

|---|---|

| Shoulder Wear Both Shoulders wearing faster than the centre of the tread | |

| Under-inflation | |

| Repeated high-speed cornering | |

| Improper matching of rims and tyres | |

| Tyres haven't been rotated recently | |

| Centre Wear The centre of the tread is wearing faster than the shoulders | |

| Over-inflation | |

| Improper matching of rims and tyres | |

| Tyres haven't been rotated recently | |

| One-sided wear One side of the tyre wearing unusually fast | |

| Improper wheel alignment (especially camber) | |

| Tyres haven't been rotated recently | |

| Spot wear A part (or a few parts) of the circumference of the tread are wearing faster than other parts. | |

| Faulty suspension, rotating parts or brake parts | |

| Dynamic imbalance of tyre/rim assembly | |

| Excessive runout of tyre and rim assembly | |

| Sudden braking and rapid starting | |

| Under inflation | |

| Diagonal wear A part (or a few parts) of the tread are wearing diagonally faster than other parts. | |

| Faulty suspension, rotating parts or brake parts | |

| Improper wheel alignment | |

| Dynamic imbalance of tyre/rim assembly | |

| Tyres haven't been rotated recently | |

| Under inflation | |

| Feather-edged wear The blocks or ribs of the tread are wearing in a feather-edge pattern | |

| Improper wheel alignment (faulty toe-in) | |

| Bent axle beam |

Checking your tyres.

It's amazing that so many people pay such scant attention to their tyres. If you're travelling at 70mph on the motorway, four little 20-square-centimetre pads of rubber are all that sits between you and a potential accident. If you don't take care of your tyres, those contact patches will not be doing their job properly. If you're happy with riding around on worn tyres, that's fine, but don't expect them to be of any help if you get into a sticky situation. The key of course, is to check your tyres regularly. If you're a motorcyclist, do it every night before you lock the bike up. For a car, maybe once a week. You're looking for signs of adverse tyres wear (see the section above). You're looking for splits in the tyre sidewall, or chunks of missing rubber gouged out from when you failed to negotiate that kerb last week. More obvious things to look for are nails sticking out of the tread. Although if you do find something like this, don't pull it out. As long as it's in there, it's sealing the hole. When you pull it out, then you'll get the puncture. That doesn't mean I'm recommending you drive around with a nail in your tyre, but it does mean you can at least get the car to a tyre place to get it pulled out and have the resulting hole plugged. The more you look after your tyres, the more they'll look after you.

Lies, damn lies, and tyre pressure gauges.

Whilst on the subject of checking your tyres, you really ought to check

the pressures once every couple of weeks too. Doing this does rather

rely on you having, or having access to a working, accurate tyre

pressure gauge. If you've got one of those free pencil-type gauges that

car dealerships give away free, then I'll pop your bubble right now and

tell you it's worth nothing. Same goes for the ones you find on a

garage forecourt. Sure they'll fill the tyre with air, but they can be

up to 20% out either way. Don't trust them. Only recently - since about

2003 - have I been able to trust digital gauges. Before that they were

just junk - I had one which told me that the air in my garage was at

18psi with nothing attached to the valve. That's improved now and

current-generation digital gauges are a lot more reliable. One thing to

remember with digital gauges is to give them enough time to sample the

pressure. If you pop it on and off, the reading will be low. Hold it on

the valve cap for a few seconds and watch the display (if you can).

Generally speaking you should only trust a decent, branded pressure

gauge that you can buy for a small outlay - $30 maybe - and keep it in

your glove box. The best types are the ones housed in a brass casing

with a radial display on the front and a pressure relief valve. I keep

one in the car all the time and it's interesting to see how badly out

the other cheaper or free ones are. My local garage forecourt has an

in-line pressure gauge which over-reads by about 1.5psi. This means

that if you rely on their gauge, your tyres are all 1.5psi short of

their recommended inflation pressure. That's pretty bad. My local

garage in England used to have one that under-read by nearly 6 psi,

meaning everyone's tyres were rock-hard because they were 6psi

over-inflated. I've yet to find one that matches my little calibrated

gauge.

One reader pointed something else out to me. Realistically even a cheap

pressure gauge is OK provided it is consistent. This is easy to check

by taking three to five readings of the same tyre and confirming they

are all the same, then confirming it reads (consistently) more for

higher pressure and less for lower pressure.

One last note : if you're a motorcyclist, don't carry your pressure

gauge in your pocket - if you come off, it will tear great chunks of

flesh out of you as you careen down the road....

Tyre pressure and gas-mileage.

For the first two years of our new life in America, I'd take our Subaru

for its service, and it would come back with the tyres pumped up to

40psi. Each time, I'd check the door pillar sticker which informed me

that they should be 32psi front and 28psi rear, and let the air out to

get to those values. Eventually, seeing odd tyre wear and getting fed

up of doing this, I asked one of the mechanics "why do you always

over-inflate the tyres?" I got a very long and technical response which

basically indicated that Subaru are one of the manufacturers who've

never really adjusted their recommended tyre pressures in line with new

technology. It seems that the numbers they put in their manuals and

door stickers are a little out of date. I'm a bit of a skeptic so I

researched this on the Internet in some of the Impreza forums and chat

rooms and it turns out to be true. So I pumped up the tyres to 40psi

front and rear, as the garage had been doing, and as my research

indicated. The result, of course, is a much stiffer ride. But the odd

tyre wear has gone, and my gas-mileage has changed from a meagre

15.7mpg (U.S) to a slightly more respectable 20.32 mpg (U.S). That's

with mostly stop-start in-town driving. Compare that to the official

quoted Subaru figures of 21mpg (city) and 27mpg (freeway) and you'll

see that by changing the tyre pressures to not match the manual and

door sticker, I've basically achieved their quoted figures.

So what does this prove? Well for one it proves that tyre pressure is

absolutely linked to your car's economy. I can get an extra 50 miles

between fill-ups now. It also proves that it's worth researching things

if you think something is a little odd. It does also add weight to the

above motto about not trusting forecourt pressure gauges. Imagine if

you're underfilling your tyres because of a dodgy pressure gauge - not

only is it dangerous, but it's costing you at the pump too.

What's the "correct" tyre pressure?

How long is a piece of string?

Seriously though, you'll be more likely to get a sensible answer to the

length of a piece of string than you will to the question of tyres

pressures. Lets just say a good starting point is the pressure

indicated in the owner's manual, or the sticker inside the driver's

side door pillar. I say 'starting point' because on every car I've

owned, I've ended up deviating from those figures for one reason or

another. On my Subaru Impreza, as outlined above, I got much better gas

mileage and no difference in tyre wear by increasing my pressures to

40psi. On my Honda Element, I cured the vague handling and

outer-tyre-edge wear by increasing the pressures from the

manufacturer-recommended 32/34psi front and rear respectively, to 37psi

all round. On my Audi Coupe I cured some squirrelly braking problems by

increasing the pressure at the front from 32psi to 36psi. On my really

old VW Golf, I cured bad fuel economy and vague steering by increasing

the pressures all-round to 33psi.

So what can you, dear reader, learn from my anecdotes? Not much really.

It's pub-science. Ask ten Subaru Impreza owners what they run their

tyres at and you'll get ten different answers. It depends on how they

drive, what size wheels they have, what type of tyres they have, the

required comfort vs. handling levels and so on and so forth. That's why

I said the sticker in the door pillar is a good starting point. It's really up to you to search the internet and ask around for information specific to your car.

The Max. Pressure -10% theory.

Every tyre has a maximum inflation pressure stamped on the side

somewhere. This is the maximum pressure the tyre can safely achieve

under load. It is not the pressure you should inflate them to.

Having said this, I've given up using the door pillar sticker as my

starting point and instead use the max.pressure-10% theory. According

to the wags on many internet forums you can get the best performance by

inflating them to 10% less than their recommended maximum pressure (the

tyres, not the wags - they already haves inflated egos). It's a vague

rule of thumb, and given that every car is different in weight and

handling, it's a bit of a sledgehammer approach. But from my experience

it does seem to provide a better starting point for adjusting

tyre pressures. So to go back to my Subaru Impreza example, the maximum

pressure on my Yokohama tyres was 44psi. 10% of that is 4.4, so

44-4.4=39.6psi which is about where I ended up. On my Element, the

maximum pressure is 40psi so the 10% rule started me out at 36psi. I

added one more to see what happened and it got better. Going up to

38psi and it definitely went off the boil, so for my vehicle and my

driving style, 37psi on the Element was the sweet spot.

The other alternative - don't mess with your pressures at all

So - raising the pressure can extend a tyre's life because there is now less rubber contact with the road, the tyre is stiffer and therefore heats up less so lasts longer and less friction with the road gives greater MPG. Also, less sidewall flex will give a more positive feeling of steering accuracy but it can result in less ultimate grip and sudden unexpected loss of grip at the limit of adhesion. Raising or lowering tyre pressures too much either side of manufacturers recommendations could be at the expense of a less safe, more uncomfortable vehicle. So should we take all vehicle manufacturers recommendations as being absolutely correct? Remember that thousands of hours go into the development and testing of a car. If you've dicked around with your tyre pressures and still don't think it's right, go back to the door pillar sticker and try that again - you could be surprised.

| Like the site? Help Chris buy a bike. The page you're reading is free, but if you like what you see and feel you've learned something, throw me a $5 bone as a token of your appreciation. Help me buy the object of my desire. |

Nitrogen inflation

Nitrogen

inflation (nitrogen filled tyres) is one of those topics that gets

discussed in car circles a lot. Some people swear by it, whilst others

consider it to be an expensive rip off. So what's the big idea? Well

there are two common theories on this.

Nitrogen

inflation (nitrogen filled tyres) is one of those topics that gets

discussed in car circles a lot. Some people swear by it, whilst others

consider it to be an expensive rip off. So what's the big idea? Well

there are two common theories on this.

Theory 1: nitrogen molecules are larger than oxygen molecules

so they won't permeate through the rubber of the tyre like oxygen will,

and thus you'll never lose pressure over time due to leakage. The fact

is any gas will leak out of a tyre if its at a higher pressure

than the ambient pressure outside. The only way to stop it is a

non-gas-permeable membrane lining the inside of the tyre.

The science bit:

Water is about half the size of either nitrogen or oxygen, so it might

diffuse out of the tyre faster, but it would have to be much, much

faster to make a difference. Tyres can leak 1-2 psi a month at the

extreme end of the scale although it's not clear how much of that is by

permeation through the rubber, and how much is through microscopic

leaks of various sorts. For a racing tyre to lose significant water

during its racing lifetime (maybe an hour or so for Formula 1), the

permeation rate would have to be hundreds of times faster than

oxygen or nitrogen, so that pretty much cancels out the idea that it's

the molecule size that makes the difference.

Theory 2: Nitrogen means less water vapour.

This is more to do with the thermal properties than anything else.

Nitrogen is an inert gas; it doesn't combust or oxidise. The process

used to compress nitrogen eliminates water vapor and that's the key to

this particular theory. When a tyre heats up under normal use, any

water vapour inside it also heats up which causes an increase in tyre

pressure. By removing water vapor with a pure nitrogen fill, you're

basically going to allow the tyre to stay at a more constant pressure

irrespective of temperature over the life of the tyre. In other words,

your tyre pressures won't change as you drive.

The science bit: The van der Waals gas equation

provides a good estimate for comparing the expansions of oxygen and

nitrogen to water. If you compare moist air (20°C, 80% RH) to nitrogen,

you'll find that going up as far as 80°C results in the moist air

increasing in pressure by about 0.01 psi less per litre volume than

nitrogen. Moist air will increase in pressure by 7.253psi whereas

nitrogen will increase in pressure by 7.263psi. Even humid air has only

a small amount of water in it (about 2 mole % which means about 2% by

volume), so that all puts a bit of a blunt tip on the theory that it's

the differences in thermal expansion rates that give nitrogen an

advantage. In fact it would seem to suggest that damp air is marginally

better than nitrogen. Go figure.

So which option is right - smaller molecules, or less water vapour? It would seem neither. A reader of this site had a good thought on the whole nitrogen inflation thing. He wrote: Some racer who did not know the details of chemistry and physics thought that nitrogen would be better because (insert plausible but incorrect science here) and he started using nitrogen. He won some races and word got out that he was using nitrogen in his tyres. Well, it is not expensive to use nitrogen in place of air, so pretty soon everyone was doing it. Hey, until I hear a reason that makes good scientific sense, this explanation seems just as good.

Nitrogen inflation is

nothing new - the aerospace world has been doing it for years in

aircraft tyres. Racing teams will also often use nitrogen inflation,

but largely out of conveience rather than due to any specific

performance benefit, which would tend to fit with the armchair science

outlined above. Nitrogen is supplied in pressurised tanks, so no other

equipment is needed to inflate the tyres - no compressors or generators

or anything.

So does it make a difference to drivers in the

real world? Well consider this; The air you breathe is already made up

of 78% nitrogen. The composition is completed by 21% oxygen and tiny

percentages of argon, carbon dioxide, neon, methane, helium, krypton,

hydrogen and xenon. The kit that is used to generate nitrogen for road

tyres typically only gets to about 95% purity. To get close to that in

your tyres, you'd need to inflate and deflate them several times to

purge any remaining oxygen and even then you're only likely to get

about 90% pure nitrogen. So under ideal conditions, you're increasing

the nitrogen content of the gas in the tyre from 78% to 90%. Given that

nitrogen inflation from the average tyre workshop is a one-shot deal

(no purging involved) you're more likely to be driving around with 80%

pure nitrogen than 90%. That's a 2% difference from bog standard air.

On top of that, nitrogen inflation doesn't make your tyres any less

prone to damage from road debris and punctures and such. It doesn't

make them any stronger, and if you need to top them up and use a

regular garage air-line to do it, you've diluted whatever purity of

nitrogen was in the tyres right there. For $30 a tyre for nitrogen

inflation, do you

think that's worth it? For all the alleged benefits of a nitrogen fill,

you'd be far better off finding a tyre change place that has a

vapour-elimination system in their air compressor. If they can pump up

your tyres with dry air, you'll get about the same benefits as you would with a nitrogen inflation but for free.

TPMS - Tyre Pressure Monitor Systems.

For those of you who live in America and are in to cars, you'll no doubt remember the Ford Explorer / Firestone Bridgestone lawsuits of the early 21st century. A particular variety of Firestone tyre, sold as standard on Ford Explorers, had a nasty knack of de-laminating at speed causing high-speed blowouts, which, because the Explorer was an S.U.V, resulted in high-speed rollover accidents. After the smoke cleared, it turned out that the tyres were particularly susceptible to running at low-pressure. Where most tyres could handle this, the Firestones could not, heated up, delaminated and blammo - instant lawsuit.

The NHTSA ruling.

The American

National Highways and Transport Safety Association made some sweeping

regulatory changes in 2002 because of the Ford Explorer case. Section

13 of the Transportation Recall Enhancement, Accountability and

Documentation (TREAD) Act, required the Secretary of Transportation to

mandate a warning system in all new vehicles to alert operators when

their tyres are under inflated.

After extensive study, NHTSA determined that a direct tyre pressure

monitoring system should be installed in all new vehicles. In a "return

letter" issued after meetings with the auto industry, the Office of

Management and Budget (OMB) demurred, claiming its cost-benefit

calculations provided a basis for delaying a requirement for direct

systems. The final rule, issued May 2002, would have allowed auto

makers to install ineffective TPMS and would have left too many drivers

and passengers unaware of dangerously underinflated tyres. The full

text of the various rulings and judgments, along with a lot more NHTSA

information on the subject can be found at this NHSA link.

Indirect TPMS

Indirect TPMS works without actually changing anything in the wheel or tyre. It relies on a component of the ABS system on some cars - the wheel speed sensors. Indirect TPMS reads the wheel speeds from all 4 ABS sensors and compares them. If one wheel is rotating at a different rate to the other three, it means the tyre pressure is different and the onboard computer can warn you that one tyre is low. Indirect systems don't work if you're losing pressure in all four tyres at the same rate because there is no differential between the rotations. Typically losing pressure in all tyres at once is a result of either incredibly bad luck or driving over a police spike strip.

Current / First / Second generation Direct TPMS.

The current generation of direct tyre pressure monitoring systems all

work on the same basic principle, but have two distinctly different

designs. The idea is that a small sensor/transmitter unit is placed in

each wheel, in the airspace inside the tyre. The unit monitors tyre

pressure and air temperature, and sends information back to some sort

of central console for the driver to see. This is a prime example of

trickle-down technology from motor racing. Formula 1 teams have been

using this technology for years and now it's coming to consumer

vehicles.

At its most basic, the system has one or more lights in the cabin

and/or a buzzer or some other sound. When one of the tyre pressure

monitors registers over-temperature or under-inflation, the driver is

alerted by a sound and a light indicating the problem. On more

up-market systems, the indicator will show which tyre has the problem.

Strap-on sensors.

The first type of sensor is a strap-on type. It's about the size of

your thumb and it clamped to the inside of the wheel rim with a steel

radial belt. SmarTire

manufacture an aftermarket kit that can be fitted to most vehicles.

Typically these sensors weigh in at about 42g (about 1½ ounces) and the

load is centred on the wheel rim. Normal wheel-balancing procedures can

compensate for these devices. The downside is that you have the

potential for the steel strap to fail and start flailing about inside

your tyre, and if you do get a flat, the location of the sensor means

it will be crushed and destroyed within the first wheel rotation of

your tyre going flat. Then again, these devices are there to warn you

of weird operating conditions. They cannot predict a blowout.

Valve-stem sensors.

The second type of sensor is a small block which forms part of the

inside of the tyre valve stem. It's a little smaller than the strap-on

type and doesn't have the associated steel band to go with it.

Manufacturers include Autodax

TRW Automotive and Pacific Industrial Corp. You'll find these on GM,

Subaru, Honda and Toyota vehicles amongst others. These sensors are

lighter and weigh about 28g (an ounce). Because they are smaller and

are part of the valve stem itself, they are mounted to one side of the

wheel rim. Again, regular wheel-balancing can account for this weight.

The disadvantage of this system is that because of its

proximity to the side of the wheel, a ham-fisted tyre-changer can

easily destroy the sensor with the machine that is used to take tyres

off the rims. Also, when re-fitting the tyres, the tyre bead itself, if

not correctly located, can crush the sensor. Finally, because the valve

passes through the TPMS unit, you can't use quick-seal aerosol type

flat tyre remedies because the gunk screws up the transmitters.

Dust-cap sensors.

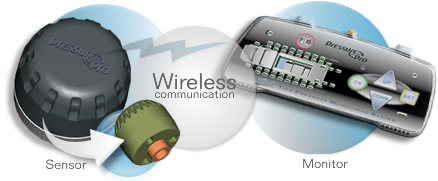

The third type of sensor is perhaps the easiest to use as an add-on item. PressurePro

sell a system where the sensors are actually built in to the dust caps

that you screw on to your tyre valves. In their system, the in-car

monitor ($199 at the time of writing) plugs into the 12v accessory

socket so it requires no in-vehicle wiring. The PressurePro sensors

send readings to the in-car unit every 7 seconds via wireless RF. The

system alerts you if the pressure in any tyre drops 12.5% below its

baseline pressure - the pressure the tyre was at when the sensor cap

was first screwed on. 12.5% is actually quite a lot. For a passenger

car tyre running at 34psi, 12.5% represents a drop of 4.25; psi. Whilst

that's definitely into the danger zone - the reason for TPMS in the

first place - a drop of 1psi is enough to begin to affect tyre

temperature and gas mileage. Note: the PressurePro system doesn't

monitor tyre temperature.

The third type of sensor is perhaps the easiest to use as an add-on item. PressurePro

sell a system where the sensors are actually built in to the dust caps

that you screw on to your tyre valves. In their system, the in-car

monitor ($199 at the time of writing) plugs into the 12v accessory

socket so it requires no in-vehicle wiring. The PressurePro sensors

send readings to the in-car unit every 7 seconds via wireless RF. The

system alerts you if the pressure in any tyre drops 12.5% below its

baseline pressure - the pressure the tyre was at when the sensor cap

was first screwed on. 12.5% is actually quite a lot. For a passenger

car tyre running at 34psi, 12.5% represents a drop of 4.25; psi. Whilst

that's definitely into the danger zone - the reason for TPMS in the

first place - a drop of 1psi is enough to begin to affect tyre

temperature and gas mileage. Note: the PressurePro system doesn't

monitor tyre temperature.

I've been in contact with one of the

engineering types at PressurePro and will be reviewing their system for

these pages in August 2006.

One concern I had about this system was

the construction of their dustcaps themselves. Built wrong, they could

cause the one thing they're designed to prevent - tyre deflation. How?

In order for the dustcap-monitor to work, it has to hold the valve stem

open once it is screwed on (see also The Low Tech Approach

below). If the unit should crack or break under duress whilst it is

holding the valve stem open, it could lead to tyre deflation. After

speaking to a PressurePro rep, he informed me that there are three

failsafes built into the dustcap to prevent this from happening, even

if the cap itself begins to distort. The caps are tested up to 300°F

(148°C) and down to -40°F (-40°c) for distortion and brittle fracture.

Each cap costs $50 retail at the time of writing, so judge for yourself

if they're likely to be built better than the low tech approach which

cost $19 for four. See the product review page for my test of the PressurePro system.

Driver displays.

As I mentioned above, the driver displays range from the über simple

buzzer and light, to items which would look at home on the bridge of

the starship Enterprise. In the SmarTire picture above, you can see

their sensor has 4 lights on it to the right of the box - an example of

the basic system. The Autodax image shows a more complex system which

shows actual pressures and temperatures as well. SmarTire have a second

generation display available now which shows a graphic representation

of the vehicle along with the problem tyre. Their new system can be set

to trigger at specific temperatures and inflation pressures. For

example it can go off when the tyre gets too hot, when the pressure

goes below a set threshold, or the pressure gets a specified amount

below the "starting" pressure (eg if it loses 1psi of pressure). This

is SmarTire's second-generation display showing some of their operating

modes:

The limits of what TPMS can do.

All TPMS systems have limits. These are usually around ±1.5 PSI/.1 BAR

in pressure accuracy, and ±5.4°F/3°C temperature accuracy. They cannot warn you of an impending blowout. Tyre blowouts are caused by instantaneous failure of the tyre. However

they can tell you about the symptoms that lead to blowouts, and that is

the primary reason for having TPMS. Tyre failures are usually preceded

by long periods of running at lower-than-acceptable pressures - TPMS

would warn you about that. When the tyre pressure is low, the sidewall

flexes a lot more, generating more heat - TPMS can tell you about that

too.

Typically, tyre pressure is transmitted as soon as your

vehicle starts moving. Pressure data is then transmitted every 4-6

minutes randomly, although the sensors read tyre pressure every 7

seconds or so. If the new pressure reading differs from the last

transmitted pressure by more than 3 PSI/.21 BAR, then the data is

transmitted immediately to alert you of a problem. In some systems, the

car's onboard computer has preset limits so rather than measuring a

change, the system simply alerts you when one of the tyres drops below

the preset limit.

Tyre temperature is also normally transmitted as soon as the vehicle

starts moving. As with pressure data, temperature data is then

transmitted every 4-6 minutes randomly. Again the sensors will read the

temperature more frequently, however the system will only alert you if

the temperature exceeds 80°C/176°F.

The down-side of current TPMS.

TPMS sensors need power to work. All the current sensors use batteries.

Whilst these are rated for about 5 years use, or 250,000 miles, the

batteries are not replaceable

in any system. The manufacturers don't want a battery cover to come

loose and start zipping around inside your tyre. For one it is

dangerous to the inside of the tyre and for another, if the battery

compartment opened, the battery would come out and you'd lose all

sensor data for that wheel. As a result, the batteries are built-in to

the sealed unit during manufacture. If you get a dead sensor, you need

to buy a whole new one. Also, you know what batteries are like in

extreme cold and extreme hot - bear that in mind if you regularly park

in snow and ice....

Currently, there are no laws mandating

manufacture dates to be put on these third-party systems. So if you buy

one from a store, it could be brand new, or it could have been sitting

on the shelf for a year. You've been warned.

Rotating your tyres or using snow tyres - what you need to know when using TPMS.

All factory-fit TPMS systems are registered at the factory to the

vehicle. The onboard computer stores a unique transponder ID for each

unit along with its position on the car - front left or right, rear

left or right for example. If you change wheels in the winter to wheels

with snow tyres on them, you either need to move the TPMS sensors to

the corresponding new wheels, or have a duplicate set. Same goes for

rotating your tyres - if you do front to back rotation for example, the

car's computer still reads the TPMS signals but the sensors it believes

are on the front are now on the rear and vice versa. For vehicles with

even tyre pressures all around, this makes no difference unless you

have a system which can tell you which

tyre is deflating. If you have a vehicle where the front pressures are

supposed to be lower than the rear, the onboard pressure limits will be

set accordingly and the underinflation alarms will be skewed.

Particularly at the front - the sensors will be expecting higher

pressure because they're registered as being on the rear wheels. You

could end up with a constant TPMS alarm.

So how to get around this?

There is no easy way. Some vehicles have onboard re-learning

capabilities, where you can get the vehicle into a mode where you can

teach it the location of the sensors in a particular order. Others

require reprogramming through the OBDII port. Either way you need

specialist equipment (such as those sold by Bartec)

to stimulate the TPMS transponders in order and then reprogram the

vehicle accordingly. The general procedure starts at the front left

tyre once the vehicle is in 'learn' mode and then works clockwise

around it. For wireless type reprogramming, the vehicle waits for the

first transponder code, which it receives when you stimulate the sensor

using the special tool, then waits for the second code and so on. For

wired-type reprogramming, the tool stores the 4 transponder codes in

order then uploads them to the car's computer once connected through

the OBD II port.

It's something to bear in mind if you have TPMS on

your vehicle - winter wheels, tyre rotations - anything that moves a

sensor from it's pre-registered location on the vehicle - can cause

problems.

Next-generation TPMS.

Several

companies are working on the battery problem for the sensor modules. As

I mentioned above, the basic pitfall of all existing systems is that at

some point, the battery will wear out, and you'll need a new sensor.

There are a few competing, emerging technologies right now trying to

tackle the problem of perfecting transmitter-sensors that don't require

a battery..

The Pera Piezotag

system relies on the inherent properties of piezoelectric materials -

that is a material which generates current when pressure is applied to

it. The inside of a tyre is constantly at pressure so it seems

reasonable that a correctly-manufactured piezoelectric wafer could

generate enough current to operate the sensor just from the pressure

inside the tyre.

The ALPS Batteryless TPMS system (licenced from IQ Mobil,

a small German R&D company) is similar to an RFID chip in that it

gets its power from the radio signal which interrogates it. Current

systems, (including the Pera proposal) are classified as "active"

transmitter / receiver systems. The sensors transmit signals of their

own accord and the in-car receiver picks them up. The ALPS system is a

"passive" RFID transceiver system. The sensors remain dormant and

un-powered until the in-car transceiver sends a high-power short-range

radio signal out which basically carries a "tell me your status"

command. The RF power in the radio signal is enough to cause the RFID

unit in the sensor to power up, take a reading, transmit it and power

down. Clever eh? The downside of this system is that it's likely to be

pricey compared to others coming to the market. There are 9 pcbs in

their system; one in each wheel, one in each wheel arch and one in the

console.

Transense Technologies

in England are licensing their technology to SmarTire, Michelin and

Honeywell. Unlike the Alps system, Transense's system has only one PCB

and employs passive surface acoustic wave sensors (piezo-based again)

at the inner end of each tyre valve. Their sensors monitor both

pressure and temperature. It's worth noting that Transense hold the

patent for resonant SAW technology which expires in 2019. Pera were

exposed to this technology in the early 90's and have since come out

with their own Piezotag system (see above). Coincidence?

Michelin has an inductive (125kHz) system for trucks developed for them by TI, Goodyear and Siemens have a similar technology system for passenger cars. Qinetic (formerly DERA / RAE Farnborough) also have an offering.

The low-tech approach.

If all

this electronic wizardry seems too much for you, you can always go to

the low-tech approach. Valve-cap pressure sensors. These are available

over-the-counter at just about any car parts store and are about as

simple a device as you can get. You inflate your tyre, and replace the

dust cap on the valve with one of these. If it shows green, you're OK.

If it shows yellow, your tyres have lost some pressure. If it shows

red, your tyres are dangerously underinflated. This system does of

course require you to walk around the car and check each time you want

to drive off.

There are some drawbacks to this system which you should be aware of.

For the pressure sensor to read the tyre pressure, it has to depress

the valve stem when its screwed on. This means that the tyre valve is

no longer the thing keeping the air in your tyre - it's now the seal

between this pressure cap and the screw threads. If it's not snug, it

will leak slowly and let air out of your tyre. Secondly, there's the

question of balance. If you use these screw-on caps, you should get

your wheels re-balanced afterwards because it's adding weight to the

rim. Third there's the question of durability - it's better for one of

these things to come off completely if you hit a pothole because then